How (and why) to document the assumptions underlying your product

Making a product people want is hard. Successful products often look like strokes of genius or incredible luck – things you can’t just buy. Wouldn’t it be great if there were a way to make consistent, fast progress toward product success?

Turns out there is. A disciplined approach to product management works, and if you look behind most “overnight success” stories, you’ll find years of disciplined effort. And while every product expert will have their own set of tricks for each part, the essential principles of disciplined product management are so simple, I can list them right here:

- Know that to succeed, your product must be desirable, feasible, and viable.

- Identify your assumptions – the working theories of how your product will be all of these.

- Iteratively test and refine your assumptions.

- Prioritize testing your most prevalent and uncertain assumptions.

In this post, I’ll explain how these pieces fit together to enable a disciplined approach to some of the biggest challenges faced by ambitious companies.

Hope is not a strategy

Some of the best products of all time seem just plain lucky. Facebook started at Harvard, and its exclusivity and prestige drove incredible adoption. Viagra was originally studied for heart disease, but had an unexpected effect on male study participants.

On the other hand, lots of successful products are enabled by uniquely deep knowledge about their market–they’re just plain smart. Snapchat understood the challenges of permanent social media and solved them in a way that frees young people to share much more than they could before. Nosefrida understood baby anatomy and the priorities of harried parents and made the Snotsucker, a huge success despite its goofy name. (Never heard of it? Ask anyone who’s had a baby in the last 5 years.)

So if you want to make a successful product, you want to be both lucky and smart.

What’s the strategy for being lucky? It’s not hope or positive thinking. Statistically, the only thing you can do to increase your chance of getting lucky is to take lots of shots on goal.

What’s the strategy for being smart? It’s knowing more than everyone else. And the way you get there is through relentless learning, focused on the subjects you really need to understand better.

No matter where your product is right now – from nascent idea to revenue-producing juggernaut – you want to be as lucky and smart as possible. Fortunately there’s a technique that will help you optimize both of these, if you do it right.

Iteration to the rescue

By definition, you can’t control how lucky you are. But you can control how often you roll the dice. Or as Gretzky said, “You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.”

You also can’t just will yourself to be smarter. If you’re learning chemistry or woodworking, you can study with an expert. But in competitive product markets, your best bet is often some form of trial and error. If you want to sound like a scientist, you can call this experimentation.

If you only care about luck, raw trial and error is sufficient. Take a guess at what you think the product should be, build it, and if you’re lucky it will sell like hotcakes. If that didn’t work, guess and build again. This great strategy is guaranteed to work given infinite investor dollars.

On the other hand—if you only care about being smart—then shipping is not necessary. Deep knowledge can be cultivated easily in narrow niches, where nobody interested in actually changing the world is trying to outdo you. You can append an endless series of initials after your name using this approach.

But you care about both luck and knowledge. So you’re going to iterate:

- Each iteration will be time-boxed, so you’re forced to run aggressively with your best guesses instead of overbuilding.

- Each iteration will be tested with the real market so you can learn something new from a human outside the building.

Have you ever seen a product leader (or team) write down a big to-do list of their own ideas, and say that if we build these we’ll have customers lining up to give us money? But we haven’t yet talked to any customers yet, because obviously we need the product first!

If this is the first product release, they’re wrong but they might figure it out soon. If this is the second, third, or tenth time you’ve heard the same thing, they’re misunderstanding the fundamental work of product development. This is a severe misunderstanding – about as delusional as hoping that when your beautiful daughter goes to Hollywood, a smart agent will discover her and make her a star.

But the iterations are just a structure. You also have to put the right stuff into the structure.

Picking what you iterate on

Product discovery is an unpredictable process that will always rely on luck, intuition, and educated guesses. You want to get more educated, but where to start? Like any project, the best approach is to do the riskiest stuff first.

This is at the core of any disciplined approach to a novel endeavor. In software engineering, it’s sometimes called Worst Things First. The idea is that if you do the most difficult or risky things first, you have more flexibility (in design direction, schedule, etc.) to respond when things don’t go as you’d hoped.

Here’s an example. Say I want to start a new social network. It clearly has to have a way for users to log in, so I’ll start by designing an amazing login flow. It’s gorgeous, usable, and my test users all say it’s the smoothest they’ve ever seen. Hooray! Launch.

Sadly, nobody is using my social network because it’s a ghost town, and all my effort on that login system is totally pointless unless I figure out how to motivate users to join. Instead of building that, I should have worked on better understanding what would motivate people to use my social network. Maybe the next big social network doesn’t even need a login system?

That’s why you want to test your riskiest assumptions first. And do that, you need to do two things: list your assumptions, and prioritize them by risk.

How to list your assumptions

Step back from the details of your business and pretend you’re advising another company in the same field. What will it take to have a successful product?

Let’s continue the social network example. To be a successful social network, a product has to:

- Have a significant volume of users

- Engage those users in frequent interactions via the product

- Appeal to advertisers

Then break down each of those. For example, to achieve a significant volume of users, we have to motivate the first signups. That probably means we have to start with a close-knit group that would get a lot of value from interacting with each other. We could do this like facebook did, with a single college dorm, or like twitter did, with a cadre of bay area tech elites. If we choose the “cadre of elites” approach, we have to find a group of elites we can attract. Suppose we target elite athletes by giving them a new way to engage fans by reporting on their training regimen. Then we are assuming (1) athletes want to engage their fans more, (2) they would be willing to share information about their training regimen, and (3) they would consider using our product to do that.

You might have noticed these are all assumptions you can test fairly easily by interviewing some elite athletes (if you can’t reach them to get interviews, that’s another set of assumptions to unpack). Once you break your product goals down like this, you can start to fill your iterations with experiments that shed some real light on your assumptions. But even listing out the assumptions can help you learn something. For example, if you realize that two of your assumptions contradict each other—like if you need early adopters who are both college students and have lots of disposable income—then you can step back and rework your plan.

If you’re not sure about where to start, remember that a successful product has to be desirable, feasible, and sustainable:

- Desirable: someone has to want what you’re offering. This is the main area that failed startups miss.

- Feasible: you have to be able to deliver what you’re offering. Unless your venture includes a component of hard technology, this probably isn’t a huge risk early on.

- Sustainable: the cost of delivering your offering, long-term, has to be bearable to your organization. Typically, this means you’ll sell enough to cover your operating costs. This is usually a later-stage question, but it’s surprisingly easy to convince yourself that you’re creating value when you’re really just moving it from investors to customers.

If you’re really at a loss for where to start listing your assumptions, begin with “people desire to use this product” and break it down from there. It will force you to state your best working assumptions. When you get to the assumptions that feel like going so far out on a limb that you’re really not sure they’ll seem correct in a couple of weeks, that’s what you want to test in your next iteration.

Prioritize the most prevalent and uncertain assumptions

Continuing our example, suppose you’ve got a handful of relatively specific assumptions. In the case of a social network seeded with elite athletes, we might have these among our assumptions:

- Elite athletes will use our training tracker (individually, even before there is a large crowd in our network).

- Anywhere elite athletes are posting content, their fans will follow.

- Fans will interact with each other around the athlete-provided content.

- Tennis stars have a more devoted individual fan base than Football stars.

Because we want to test the riskiest stuff first, we want to start our validation efforts with the assumptions that are most prevalent and most uncertain.

- More prevalent assumptions are those that underpin our product’s success in multiple areas. In this example, our ability to engage elite athletes individually supports all of the other assumptions we’ve listed. If we don’t succeed at engaging that critical initial user base, we’d better try a whole different approach.

- More uncertain assumptions are those that we have less confidence in. For example, once elite athletes are talking about their training experience, it sounds like a pretty safe bet that fans will want to see what they’re saying. On the other hand, because elite athletes are likely swamped by all sorts of appeals for attention, getting them to use our tracker is a fairly uncertain assumption.

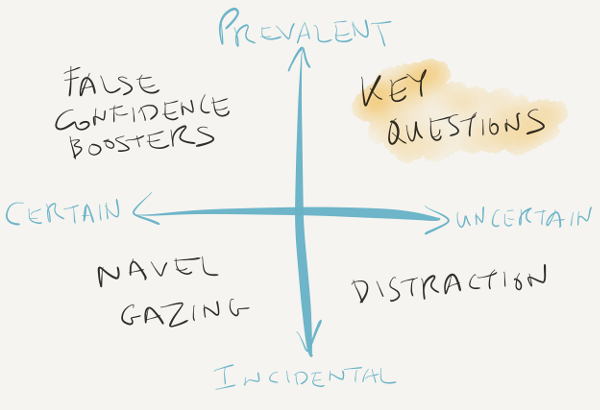

For bonus manager points, you can visualize these in a 2x2 matrix:

Now let’s see how our assumptions above fall into this matrix.

- Elite athletes will use our training tracker (individually, even before there is a large crowd in our network). — This is key question.

- Anywhere elite athletes are posting content, their fans will follow.— False confidence booster. This is prevalent, but also pretty darn likely, so proving it right would be futile.

- Fans will interact with each other around the athlete-provided content. — Also seems prevalent but pretty likely.

- Tennis stars have a more devoted individual fan base than Football stars. – Distraction, because although it’s an interesting question, either type would likely be sufficient for us to get off the ground.

Now go do it!

Writing down your assumptions is a great first step toward running your product in an efficient, disciplined way. Even though you’ve probably got an idea of what your high-priority (i.e. prevalent and uncertain) assumptions are, getting a big list written down — and identifying which ones you’re going to focus on and which you can ignore for now — can ease some of the panic you feel when there seem to be a thousand Big Important Things.

And you don’t need anything special to get started — whiteboard, post-its, google docs, or pencil and paper will do. You’ll naturally tweak the specific techniques after a few iterations!

Feedback? Questions about this or another aspect of product management? Let me know.